In my quest to better familiarize myself with the great genre films out there I rented Ridely Scott's Alien, which I have heard described as "a haunted house story in space." At the same time I came across the comic book adaptation by Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson, published by Heavy Metal. Watching the film and reading the comic on top of each other was an interesting learning process on the importance of texture in telling a story.

I came into Scott's Alien with a lot of preconceived notions. A major one, soon shattered, was that this was an action film, like latter films in the series (my introduction to these movie monsters came from the tie-in merchandise, the video games and action figures of my youth). This film is about scares. To become scary it takes its time in setting up a particular mood for the spaceship Nostromo. The first images in the film is the word "ALIEN" slowly appearing on-screen, starting with abstract lines that only fully spell the word after a few minutes. The opening of the narrative is similarly creepy and obtuse. It's just a computer turning itself on while one of the crew's space helmets stays on top of the ship's machinery. But the little things about that scene make an impact. There's the way that one bit of the ship is pumping up and down in the background and how the computer's monitor is reflected in the helmet's visor that communicates this sense of strangeness, and the distressing feeling of jeopardy that comes with it.

Scott's ability to create such an intense atmosphere assists the structure of the film, where the alien doesn't become a presence until an hour into the film. Instead we spend time with the working class crew of the Nostromo. There is abundant characterization in Alien but it's not the usual kind seen in films. Screenwriter Dan O'Bannon said he was impressed with producer Walter Hill's screenwriting technique (Hill wrote and directed The Warriors and The Driver as well as many other films). O'Bannon said it resembled "blank verse" in how perfectly simple it was. That simplicity works in Alien as we only learn about the crew of the Nostromo in how they react to the immediate actions taking place in the scene. When a face-hugged Kane is about to be taken aboard we see what kind of characters Ash and Ripley are when they go for completely opposite actions (letting the alien aboard also leads to another plot line involving Ash we see later).

One of the main reasons that precise way of storytelling works is due to the acting. Watch that scene of the crew socializing over breakfast after deep sleep and you see a collection of some of the best character actors in modern film. Harry Dean Stanton and Yaphet Kotto have an immediate chemistry as these blue collar guys. The rest of the actors are able to establish themselves with only a few bits of dialog and actions but I thought Ian Holm did the best job early on as Ash, the science officer who seems a bit...off (shades of Spock). Of course it's Sigourney Weaver as Ripley who captures our attention knowing she's the second most important thing of the entire franchise. Her performance presents a type of woman not seen much in sci-fi/fantasy films, then or now. She is focused and capable but spends no time satisfied with herself for standing out, she just is. Her Ripley makes an interesting contrast to both Lambert (Veronica Cartwright), who is more in the "scream queen" vein, and Dallas (Tom Skerritt), who starts off being the typical male lead but whose changes when all intergalactic Hell breaks loose.

There's no doubt when the chaos starts happening, it's the greatest and most remembered scene in the film. John Hurt's Kane is recovering from a facehugger attack and, recalling an earlier scene in the film, the crew is breaking bread with each other and acting very comfortable with themselves. Then a monster bursts out of Kane's chest and quickly scurries off. On the DVD commentary track Cartwright talks about how the cast, with the obvious exception of Hurt, didn't know what the chest bursting would look like. The reactions you see are not those of the characters but the actors playing those characters. The universal pop culture conscience has dulled the novelty of the scene but it's still a powerful marker between the first half of the film and the second. From there all the capital of mood Scott has built up gets cashed in. When Stanton enjoys the water from the ceiling dripping on his face it's both a beautiful and sad image, knowing what could be the only possible ending to that scene. The film's pace quickens but not by too much. There is still plenty of space between the alien's kills, space filled by O'Bannon's "characterization as plot progression." There's also a subplot about the entire alien situation being engineered by the Weyland-Yutani Corparation and its dutiful android Ash. This was added in later by Hill and listening to the commentary track O'Bannon makes it clear he didn't like his story being changed to make "a trite political statement." This is a man committed to one thing, scare the Hell out of the audience with a monster they've never seen before, and nothing else. Fortunately for O'Bannon and the audience that goal is still met. The various characters' deaths creep in with great suspense and pay off with the alien, H.R. Geiger's equally repulsive and sexy design, bolting onto the screen for only a short while. You never really see much of the alien actually slashing up anyone, usually just the gory aftermath.

The film only really feels fast when Ripley has to reach the escape ship while emergency self-destruct lights are going off. The claustrophobic sense of the Nostromo is heightened in those scenes of our heroine running down the corridors. All that and the film isn't even happy with just one climax. Rather, we get another battle between Ripley and the alien on the escape ship itself setting up the "blown into space" offensive tactic that James Cameron would basically repeat at the end of Aliens. Ripley and Jonsey the cat have to enter deep sleep after all that, a simple nap wouldn't be the come down needed after that maddening experience.

Goodwin and Simonson are telling the same story but with definite stylistic differences. It's a good comic made by great artists but suffers in comparison from not being as ambitious with its medium as Scott was with his. An "illustrated story" from Heavy Metal this book is from the time when people wanted to give the medium a more sophisticated face but were still a part of "comic-book culture," to use something I picked up from Eddie Campbell. Creators used more pages and had less content restrictions but books such as this feel closer to Marvel superhero stories than the stuff we see in graphic novels now. Of course this is still a story about an alien terrorizing a spaceship that's not necessarily a bad thing. The book is not as startling original as the film but Simonson's contributions in terms of technique still manage to astound.

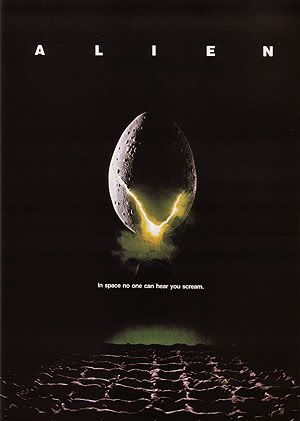

The major stylistic difference is visible from the start. The film presents its title slow and creepy. On the cover of the book the word "ALIEN' is in big yellow letters and takes up most of the cover. Goodwin and Simonson haven't created the exact opposite of what Scott did but this book does go big where Scott never does. In the film big set pieces, such as the downed ship infested with alien eggs, loom over the actors. In a Walt Simonson a comic splash page, or double splash page as used in the same scene, is loud. Alien had a beautifully subtle score by Jerry Goldsmith but those Simonson scenes look like they should be scored by John Williams. The chest bursting splash page doesn't feature a small alien coming out of Kane but rather this long snake surrounded by an almost psychedelic backdrop of blood. To pile on top of that Goodwn's narration tells us "Eruption! A scarlet shower. Of flesh. Of blood. It moves. Faster than the eye can follow..."

Fitting what is a roughly two hour film into about 60 pages would seem to be impossible. Goodwin and Simonson had no room to set the mood the film had. The intensity of scenes start much more quickly and are over faster as well. Thankfully Simonson is the kind of artist that can make sure these scenes work in a comic book format. The two pages of Harry Dean Stanton's character's death should be studied on how to organize panels and show movement as to really communicate excitement. One technique Simonson uses a lot is a row of panels in the exact same shape with only the slightest change between them (on the third page of the actual story he does it twice). Since he didn't have the breathing room Scott had Simonson found a way to create tension and release right in the moment.

Goodwin and Simonson adapt a film with a distinct feel into a comic book story that is well done but is still crafted similarly to what had come before. Things could have been different if the creators had the freedom, or at least the page count, some artists do now in creating fully realized graphic novels. This book came from a time when there were still these expectations on what a comic book, at least a genre comic book, had to be. This wasn't something the audience was watching on a giant screen. This was something they held in their hands and could close at any moment. The comic hollered certain ideas while the film whispered them but then again, the comic had a much longer way to get to you.

No comments:

Post a Comment